|

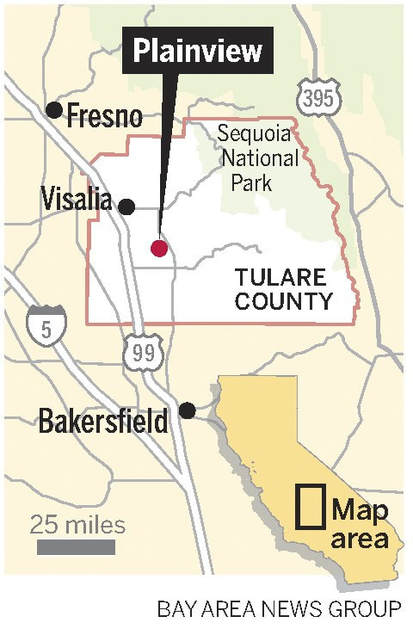

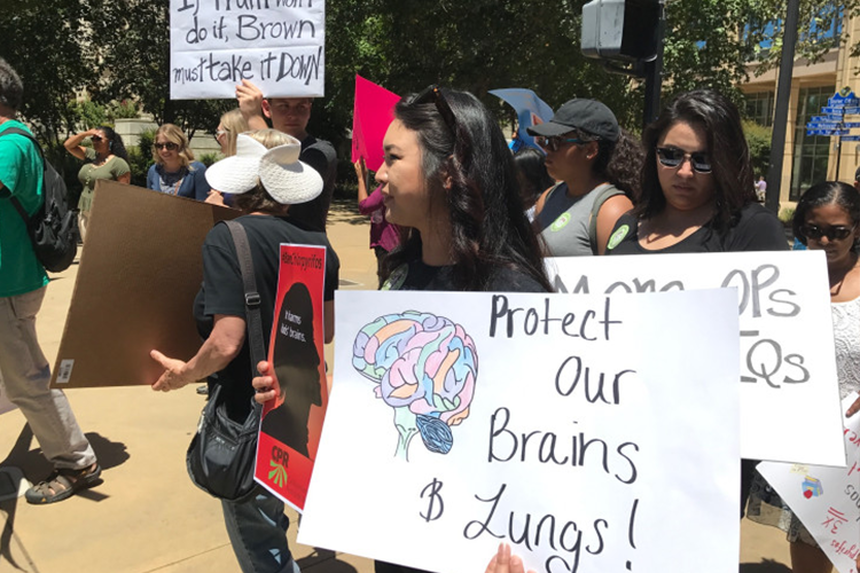

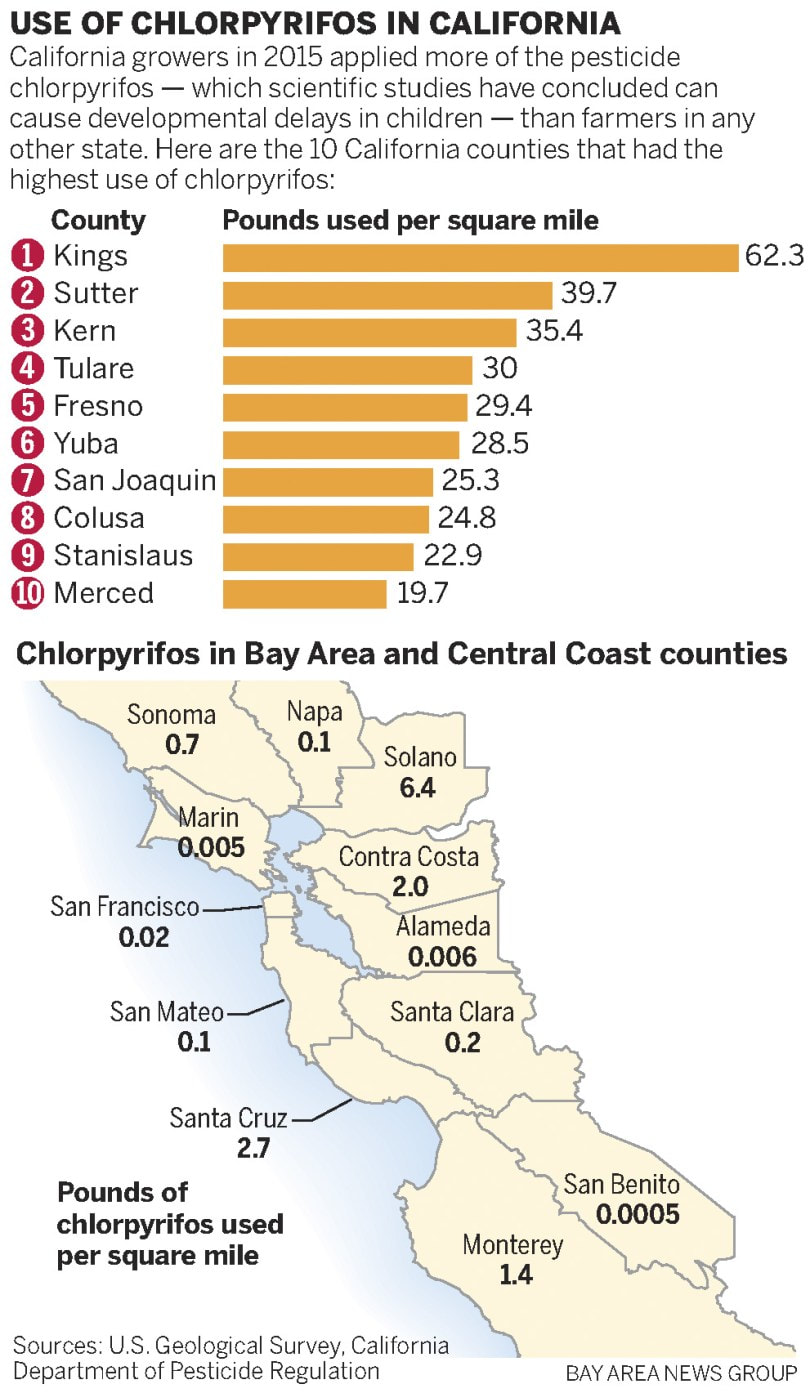

PLAINVIEW – Jesus Madrigal stared at a field of grapes across the street from his house in this dusty Central Valley town, as a chemical odor drifted toward him. “They’re too close,” he said of the grapevines. Madrigal said there were no grapes in Plainview when he moved here from Mexico two decades ago to settle in the unincorporated town of 1,000 in Tulare County. But now the grapes have moved in next door, along with the pesticides that farmers spray to kill pests that could damage the fruit. Tulare County’s fields, nestled close to heavily Latino cities and towns, are now at the center of a battle over the future of the pesticide chlorpyrifos (pronounced clor-PEER-if-oss). The chemical can induce tremors and dizziness in adults and developmental delays in children who were exposed while in their mothers’ wombs, according to multiple scientific studies.  In 2015, the last year for which statistics are available, California’s growers applied more SJM-L-PESTICIDEMAP-0818-91chlorpyrifos than farmers in any other state — mainly in the Central Valley, according to the U.S. Geological Survey and California’s pesticide usage database. Farmers use it to protect crops such as almonds and oranges from ants, stink bugs and other insects. In October 2015, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed banning all agricultural uses of chlorpyrifos. The agency had until the end of March to decide whether to outlaw the chemical based on feedback from the public and follow-up studies. On March 29, Scott Pruitt, the head of the EPA, rejected the proposal, saying that there wasn’t enough scientific evidence to deprive farmers of a needed tool or to justify EPA scientists’ follow-up studies. So now it’s up to the California Department of Pesticide Regulation, part of the California Environmental Protection Agency, to decide how much to restrict the use of chlorpyrifos in the Golden State. On Friday, the department announced that it will move toward imposing more restrictions of chlorpyrifos — such as increasing buffer zones between fields where they spray the pesticide and homes and schools. But people in the communities most affected by pesticides have mobilized to press for a ban on the use of chlorpyrifos in California. On July 12, many of these residents headed to Sacramento to call for the statewide ban, staging a spirited protest in front of the California Environmental Protection Agency. The demonstrators held signs saying “If Pruitt won’t do it, (Gov.) Brown must take it down” and “Bees are better protected than children.” Madrigal said Plainview’s growers usually spray pesticides between 2 and 3 a.m. He, his wife and their two children often wake up in the morning to a smell wafting through their house — and “it’s not the coffee,” he said. “We need to do something,” Madrigal said. “But I don’t know where to go.” In March, farmers sprayed grapes near his house with a chlorpyrifos-containing product called Lorsban Advanced, a product of Dow AgroSciences, according to a Tulare County database that tracks pesticide use. Of the 58 counties in California, Tulare County applied the fourth-highest amount of chlorpyrifos in terms of pounds per square mile in 2015, mostly to oranges, according to California’s pesticide usage database. Chlorpyrifos was once heavily used in homes and gardens across the country as an ingredient in products targeting common pests such as ants, termites and fleas. But in June 2000, the EPA banned all household uses, except for roach and ant baits in child-resistant packages. So now the pesticide is used mostly to kill pests on crops. The chemical belongs to a family of pesticides called organophosphates. People exposed to high doses often become dizzy and confused. At excessively high doses, chlorpyrifos exposure can lead to death. But federal and state regulations are supposed to keep human exposures within safe limits. “No pest control product has been more thoroughly evaluated,” a spokesperson for Dow AgroSciences said in an email. “The current regulatory safety standard for chlorpyrifos is supported by decades of robust toxicology data, and we are confident that authorized uses of chlorpyrifos products, when used as directed, offer wide margins of protection for human health and safety.” But over the past decade, several peer-reviewed studies have concluded that children exposed to very small doses of organophosphates while in the womb are more likely to have developmental problems and low performance on intelligence tests. Scientists at UC Davis found that mothers who lived within about a mile of chlorpyrifos application during their second trimester of pregnancy had three times the risk of having a child with autism. UC Berkeley scientists found that mothers living within six-tenths of a mile of organophosphate application were more likely to have children who scored lower on intelligence tests at age 7. Another study looking at urban uses of the pesticide showed that 7-year-old children in New York City exposed to chlorpyrifos in the womb also scored lower on IQ tests. These studies led the EPA’s scientists to reevaluate chlorpyrifos levels and human health. In 2015 and 2016, they released updated assessments that took into account the much lower doses associated with developmental disorders in children. So the EPA proposed a ban on all agricultural use of chlorpyrifos across the U.S. When EPA chief Pruitt rejected the proposed ban in March, many California growers were relieved. “The market demands the best-looking orange,” said Blake Mauritson, a farmer for Kaweah Lemon Co. in Tulare County. But, he said, “it seems like every day you turn around it’s harder and harder.” Kaweah uses chlorpyrifos sparingly, Mauritson said, adding that the chemical is very useful because it kills a wide variety of pests, such as ants and scale insects, so named because they look like fish scales. Growers have been using the pesticide less frequently over the past few years because it is now a restricted material in California. That means farmers have to register with the Department of Pesticide Regulation or county agricultural commissioners before they use it so that regulators can keep an eye on how much chlorpyrifos is being used. The department has been studying what levels of chlorpyrifos exposure pose risks to children and women of childbearing age. A draft of an updated assessment of the risks of chlorpyrifos that was released Friday concluded that chlorpyrifos inhalation may be unhealthy for these groups. The public can comment on the draft until Oct. 2, and then it will undergo a scientific review. The department expects to release its final assessment of chlorpyrifos risks by December. But while the draft is under review, the department plans to issue interim restrictions on chlorpyrifos application methods to county agricultural commissioners. “We’re taking a very close look at this pesticide,” said department spokesperson Charlotte Fadipe. Meanwhile, in small towns like Lindsay, seven miles northwest of Plainview, residents are stepping up their activism.

Lindsay resident Irma Medellin said her family moved to California from Mexico “because we wanted a better quality of life,” she said. But when she got here, she often felt isolated and alone. It wasn’t until she started working with fellow Lindsay residents for a migrant photography project that she learned that many people were facing problems similar to hers. So, she said, she decided “I can do something.” Medellin said she’s determined to raise awareness about the dangers of pesticides — both within her own community and beyond. “We are exposed to this pesticide because we live here,” she said. “But what about people who consume the fruit? We are all connected. Everybody needs to know.” Original story published: http://www.mercurynews.com/2017/08/19/4725501/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CLAA News

Categories

All

Archives |

|

CLAA is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit and we rely on support from our alumni, friends, and sponsors. |

About CLAA |

Alumni |

Students |

Giving Back |

Copyright © 2024 UC Berkeley Chicano Latino Alumni Association. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed